The American

The American The Wings of the Dove, Volume 1 of 2

The Wings of the Dove, Volume 1 of 2 Frost at Midnight

Frost at Midnight Morning Frost

Morning Frost The Portrait of a Lady — Volume 1

The Portrait of a Lady — Volume 1 Fatal Frost

Fatal Frost The Europeans

The Europeans The New York Stories of Henry James

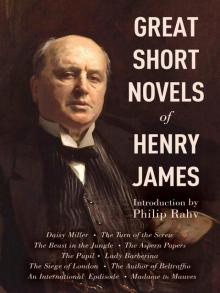

The New York Stories of Henry James Great Short Novels of Henry James

Great Short Novels of Henry James Washington Square

Washington Square The Portrait of a Lady — Volume 2

The Portrait of a Lady — Volume 2 The Ambassadors

The Ambassadors The Wings of the Dove

The Wings of the Dove The Princess Casamassima (Classics)

The Princess Casamassima (Classics) The Coxon Fund

The Coxon Fund First Frost

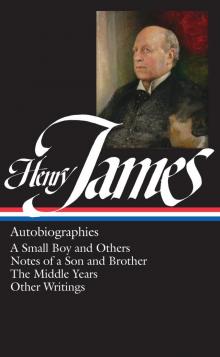

First Frost Henry James

Henry James The Daily Henry James

The Daily Henry James Travels With Henry James

Travels With Henry James The Reverberator: A Novel

The Reverberator: A Novel What Maisie Knew (Henry James Collection)

What Maisie Knew (Henry James Collection) The Outcry

The Outcry The Marriages

The Marriages The Wings of the Dove, Volume 2

The Wings of the Dove, Volume 2 The Bostonians, Vol. I

The Bostonians, Vol. I The Outcry: -1911

The Outcry: -1911 The Complete Works of Henry James

The Complete Works of Henry James Letters from the Palazzo Barbaro

Letters from the Palazzo Barbaro The Pupil

The Pupil The Bostonians, Vol. II

The Bostonians, Vol. II Pandora

Pandora Glasses

Glasses The Princess Casamassima

The Princess Casamassima What Maisie Knew

What Maisie Knew The Reverberator

The Reverberator The Golden Bowl - Complete

The Golden Bowl - Complete Confidence

Confidence Wings of the Dove (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Wings of the Dove (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) The Spoils of Poynton

The Spoils of Poynton