- Home

- Henry James

Henry James Page 18

Henry James Read online

Page 18

The great Kentucky error, however, had been the introduction into a free State of two pieces of precious property which our friends were to fail to preserve, the pair of affectionate black retainers whose presence contributed most to their exotic note. We revelled in the fact that Davy and Aunt Sylvia (pronounced An’silvy,) a light-brown lad with extraordinarily shining eyes and his straight, grave, deeper-coloured mother, not radiant as to anything but her vivid turban, had been born and kept in slavery of the most approved pattern and such as this intensity of their condition made them a joy, a joy to the curious mind, to consort with. Davy mingled in our sports and talk, he enriched, he adorned them with a personal, a pictorial lustre that none of us could emulate, and servitude in the absolute thus did more for him socially than we had ever seen done, above stairs or below, for victims of its lighter forms. What was not our dismay therefore when we suddenly learnt—it must have blown right up and down the street—that mother and son had fled, in the dead of night, from bondage? had taken advantage of their visit to the North simply to leave the house and not return, covering their tracks, successfully disappearing. They had never been for us so beautifully slaves as in this achievement of their freedom; for they did brilliantly achieve it—they escaped, on northern soil, beyond recall or recovery. I think we had already then, on the spot, the sense of some degree of presence at the making of history; the question of what persons of colour and of their condition might or mightn’t do was intensely in the air; this was exactly the season of the freshness of Mrs. Stowe’s great novel. It must have come out at the moment of our fondest acquaintance with our neighbours, though I have no recollection of hearing them remark upon it—any remark they made would have been sure to be so strong. I suspect they hadn’t read it, as they certainly wouldn’t have allowed it in the house; any more indeed than they had read or were likely ever to read any other work of fiction; I doubt whether the house contained a printed volume, unless its head had had in hand a law-book or so: I to some extent recover Mr. Norcom as a lawyer who had come north on important, difficult business, on contentious, precarious grounds—a large bald political-looking man, very loose and ungirt, just as his wife was a desiccated, depressed lady who mystified me by always wearing her nightcap, a feebly-frilled but tightly-tied and unmistakable one, and the compass of whose maternal figure beneath a large long collarless cape or mantle defined imperfectly for me of course its connection with the further increase of Albert’s little brothers and sisters, there being already, by my impression, two or three of these in the background. Had Davy and An’silvy at least read Uncle Tom?—that question might well come up for us, with the certainty at any rate that they ignored him less than their owners were doing. These latter good people, who had been so fond of their humble dependents and supposed this affection returned, were shocked at such ingratitude, though I remember taking a vague little inward Northern comfort in their inability, in their discreet decision, not to raise the hue and cry. Wasn’t one even just dimly aware of the heavy hush that, in the glazed gallery, among the sausages and the johnny-cakes, had followed the first gasp of resentment? I think the honest Norcoms were in any case astonished, let alone being much incommoded; just as we were, for that matter, when the genial family itself, installed so at its ease, failed us with an effect of abruptness, simply ceased, in their multitude, to be there. I don’t remember their going, nor any pangs of parting; I remember only knowing with wonderment that they had gone, that obscurity had somehow engulfed them; and how afterwards, in the light of later things, memory and fancy attended them, figured their history as the public complication grew and the great intersectional plot thickened; felt even, absurdly and disproportionately, that they had helped one to “know Southerners.” The slim, the sallow, the straight-haired and dark-eyed Eugene in particular haunted my imagination; he had not been my comrade of election—he was too much my senior; but I cherished the thought of the fine fearless young fire-eater he would have become and, when the War had broken out, I know not what dark but pitying vision of him stretched stark after a battle.

All of which sounds certainly like a meagre range—which heaven knows it was; but with a plea for the several attics, already glanced at, and the positive æsthetic reach that came to us through those dim resorts, quite worth making. They were scattered and they constituted on the part of such of our friends as had license to lead us up to them a ground of authority and glory proportioned exactly to the size of the field. This extent was at cousin Helen’s, with a large house and few inmates, vast and free, so that no hospitality, under the eaves, might have matched that offered us by the young Albert—if only that heir of all the ages had had rather more imagination. He had, I think, as little as was possible—which would have counted in fact for an unmitigated blank had not W. J., among us, on that spot and elsewhere, supplied this motive force in any quantity required. He imagined—that was the point—the comprehensive comedies we were to prepare and to act; comprehensive by the fact that each one of us, even to the God-fearing but surreptitiously law-breaking Wards, was in fairness to be enabled to figure. Not one of us but was somehow to be provided with a part, though I recall my brother as the constant comic star. The attics were thus in a word our respective temples of the drama—temples in which the stage, the green-room and the wardrobe, however, strike me as having consumed most of our margin. I remember, that is, up and down the street—and the association is mainly with its far westward reaches—so much more preparation than performance, so much more conversation and costume than active rehearsal, and, on the part of some of us, especially doubtless on my own, so much more eager denudation, both of body and mind, than of achieved or inspired assumption. We shivered unclad and impatient both as to our persons and to our aims, waiting alike for ideas and for breeches; we were supposed to make our dresses no less than to create our characters, and our material was in each direction apt to run short. I remember how far ahead of us my brother seemed to keep, announcing a “motive,” producing a figure, throwing off into space conceptions that I could stare at across the interval but couldn’t appropriate; so that my vision of him in these connections is not so much of his coming toward me, or toward any of us, as of his moving rapidly away in fantastic garb and with his back turned, as if to perform to some other and more assured public. There were indeed other publics, publics downstairs, who glimmer before me seated at the open folding-doors of ancient parlours, but all from the point of view of an absolute supernumerary, more or less squashed into the wing but never coming on. Who were the copious Hunts?—whose ample house, on the north side, toward Seventh Avenue, still stands, next or near that of the De Peysters, so that I perhaps confound some of the attributes of each, though clear as to the blond Beekman, or “Beek,” of the latter race, not less than to the robust George and the stout, the very stout, Henry of the former, whom I see bounding before a gathered audience for the execution of a pas seul, clad in a garment of “Turkey red” fashioned by his own hands and giving way at the seams, to a complete absence of dessous, under the strain of too fine a figure: this too though I make out in those connections, that is in the twilight of Hunt and De Peyster garrets, our command of a comparative welter of draperies; so that I am reduced to the surmise that Henry indeed had contours.

I recover, further, some sense of the high places of the Van Winkles, but think of them as pervaded for us by the upper air of the proprieties, the proprieties that were so numerous, it would appear, when once one had had a glimpse of them, rather than by the crude fruits of young improvisation. Wonderful must it clearly have been still to feel amid laxities and vaguenesses such a difference of milieux and, as they used to say, of atmospheres. This was a word of those days—atmospheres were a thing to recognise and cultivate, for people really wanted them, gasped for them; which was why they took them, on the whole, on easy terms, never exposing them, under an apparent flush, to the last analysis. Did we at any rate really vibrate to one social tone after another, or are these adventur

es for me now but fond imaginations? No, we vibrated—or I’ll be hanged, as I may say, if I didn’t; little as I could tell it or may have known it, little as anyone else may have known. There were shades, after all, in our democratic order; in fact as I brood back to it I recognise oppositions the sharpest, contrasts the most intense. It wasn’t given to us all to have a social tone, but the Costers surely had one and kept it in constant use; whereas the Wards, next door to them, were possessed of no approach to any, and indeed had the case been other, had they had such a consciousness, would never have employed it, would have put it away on a high shelf, as they put the last-baked pie, out of Freddy’s and Charley’s reach—heaven knows what they two would have done with it. The Van Winkles on the other hand were distinctly so provided, but with the special note that their provision was one, so to express it, with their educational, their informational, call it even their professional: Mr. Van Winkle, if I mistake not, was an eminent lawyer, and the note of our own house was the absence of any profession, to the quickening of our general as distinguished from our special sensibility. There was no Turkey red among those particular neighbours at all events, and if there had been it wouldn’t have gaped at the seams. I didn’t then know it, but I sipped at a fount of culture; in the sense, that is, that, our connection with the house being through Edgar, he knew about things—inordinately, as it struck me. So, for that matter, did little public Freddy Ward; but the things one of them knew about differed wholly from the objects of knowledge of the other: all of which was splendid for giving one exactly a sense of things. It intimated more and more how many such there would be altogether. And part of the interest was that while Freddy gathered his among the wild wastes Edgar walked in a regular maze of culture. I didn’t then know about culture, but Edgar must promptly have known. This impression was promoted by his moving in a distant, a higher sphere of study, amid scenes vague to me; I dimly descry him as appearing at Jenks’s and vanishing again, as if even that hadn’t been good enough—though I may be here at fault, and indeed can scarce say on what arduous heights I supposed him, as a day-scholar, to dwell. I took the unknown always easily for the magnificent and was sure only of the limits of what I saw. It wasn’t that the boys swarming for us at school were not often, to my vision, unlimited, but that those peopling our hours of ease, as I have already noted, were almost inveterately so—they seemed to describe always, out of view, so much larger circles. I linger thus on Edgar by reason of its having somehow seemed to us that he described—was it at Doctor Anthon’s?—the largest of all. If there was a bigger place than Doctor Anthon’s it was there he would have been. I break down, as to the detail of the matter, in any push toward vaster suppositions. But let me cease to stir this imponderable dust.

XIX

I TRY at least to recover here, however, some closer notation of W. J.’s aspects—yet only with the odd effect of my either quite losing him or but apprehending him again at seated play with his pencil under the lamp. When I see him he is intently, though summarily, rapidly drawing, his head critically balanced and his eyebrows working, and when I don’t see him it is because I have resignedly relinquished him. I can’t have been often for him a deprecated, still less an actively rebuffed suitor, because, as I say again, such aggressions were so little in order for me; but I remember that on my once offering him my company in conditions, those of some planned excursion, in which it wasn’t desired, his putting the question of our difference at rest, with the minimum of explanation, by the responsible remark: “I play with boys who curse and swear!” I had sadly to recognise that I didn’t, that I couldn’t pretend to have come to that yet—and truly, as I look back, either the unadvisedness and inexpertness of my young contemporaries on all that ground must have been complete (an interesting note on our general manners after all,) or my personal failure to grasp must have been. Besides which I wonder scarce less now than I wondered then in just what company my brother’s privilege was exercised; though if he had but richly wished to be discouraging he quite succeeded. It wasn’t that I mightn’t have been drawn to the boys in question, but that I simply wasn’t qualified. All boys, I rather found, were difficult to play with—unless it was that they rather found me; but who would have been so difficult as these? They account but little, moreover, I make out, for W. J.’s eclipses; so that I take refuge easily enough in the memory of my own pursuits, absorbing enough at times to have excluded other views. I also plied the pencil, or to be more exact the pen—even if neither implement critically, rapidly or summarily. I was so often engaged at that period, it strikes me, in literary—or, to be more precise in dramatic, accompanied by pictorial composition—that I must again and again have delightfully lost myself. I had not on any occasion personally succeeded, amid our theatric strife, in reaching the footlights; but how could I have doubted, nevertheless, with our large theatrical experience, of the nature, and of my understanding, of the dramatic form? I sacrificed to it with devotion—by the aid of certain quarto sheets of ruled paper bought in Sixth Avenue for the purpose (my father’s store, though I held him a great fancier of the article in general, supplied but the unruled;) grateful in particular for the happy provision by which each fourth page of the folded sheet was left blank. When the drama itself had covered three pages the last one, over which I most laboured, served for the illustration of what I had verbally presented. Every scene had thus its explanatory picture, and as each act—though I am not positively certain I arrived at acts—would have had its vivid climax. Addicted in that degree to fictive evocation, I yet recall, on my part, no practice whatever of narrative prose or any sort of verse. I cherished the “scene”—as I had so vibrated to the idea of it that evening at Linwood; I thought, I lisped, at any rate I composed, in scenes; though how much, or how far, the scenes “came” is another affair. Entrances, exits, the indication of “business,” the animation of dialogue, the multiplication of designated characters, were things delightful in themselves—while I panted toward the canvas on which I should fling my figures; which it took me longer to fill than it had taken me to write what went with it, but which had on the other hand something of the interest of the dramatist’s casting of his personæ, and must have helped me to believe in the validity of my subject.

From where on these occasions that subject can have dropped for me I am at a loss to say, and indeed have a strong impression that I didn’t at any moment quite know what I was writing about: I am sure I couldn’t otherwise have written so much. With scenes, when I think, what certitude did I want more?—scenes being the root of the matter, especially when they bristled with proper names and noted movements; especially, above all, when they flowered at every pretext into the very optic and perspective of the stage, where the boards diverged correctly, from a central point of vision, even as the lashes from an eyelid, straight down to the footlights. Let this reminiscence remind us of how rarely in those days the real stage was carpeted. The difficulty of composition was naught; the one difficulty was in so placing my figures on the fourth page that these radiations could be marked without making lines through them. The odd part of all of which was that whereas my cultivation of the picture was maintained my practice of the play, my addiction to scenes, presently quite dropped. I was capable of learning, though with inordinate slowness, to express ideas in scenes, and was not capable, with whatever patience, of making proper pictures; yet I aspired to this form of design to the prejudice of any other, and long after those primitive hours was still wasting time in attempts at it. I cared so much for nothing else, and that vaguely redressed, as to a point, my general failure of acuteness. I nursed the conviction, or at least I tried to, that if my clutch of the pencil or of the watercolour brush should once become intense enough it would make up for other weaknesses of grasp—much as that would certainly give it to do. This was a very false scent, which had however the excuse that my brother’s example really couldn’t but act upon me—the scent was apparently so true for him; from the moment my small “interest in

art,” that is my bent for gaping at illustrations and exhibitions, was absorbing and genuine. There were elements in the case that made it natural: the picture, the representative design, directly and strongly appealed to me, and was to appeal all my days, and I was only slow to recognise the kind, in this order, that appealed most. My face was turned from the first to the idea of representation—that of the gain of charm, interest, mystery, dignity, distinction, gain of importance in fine, on the part of the represented thing (over the thing of accident, of mere actuality, still unappropriated;) but in the house of representation there were many chambers, each with its own lock, and long was to be the business of sorting and trying the keys. When I at last found deep in my pocket the one I could more or less work, it was to feel, with reassurance, that the picture was still after all in essence one’s aim. So there had been in a manner continuity, been not so much waste as one had sometimes ruefully figured; so many wastes are sweetened for memory as by the taste of the economy they have led to or imposed and from the vantage of which they could scarce look better if they had been current and blatant profit. Wasn’t the very bareness of the field itself moreover a challenge, in a degree, to design?—not, I mean, that there seemed to one’s infant eyes too few things to paint: as to that there were always plenty—but for the very reason that there were more than anyone noticed, and that a hunger was thus engendered which one cast about to gratify. The gratification nearest home was the imitative, the emulative—that is on my part: W. J., I see, needed no reasons, no consciousness other than that of being easily able. So he drew because he could, while I did so in the main only because he did; though I think we cast about, as I say, alike, making the most of every image within view. I doubt if he made more than I even then did, though earlier able to account for what he made. Afterwards, on other ground and in richer air, I admit, the challenge was in the fulness and not in the bareness of aspects, with their natural result of hunger appeased; exhibitions, illustrations abounded in Paris and London—the reflected image hung everywhere about; so that if there we daubed afresh and with more confidence it was not because no-one but because everyone did. In fact when I call our appetite appeased I speak less of our browsing vision, which was tethered and insatiable, than of our sense of the quite normal character of our own proceedings. In Europe we knew there was Art, just as there were soldiers and lodgings and concierges and little boys in the streets who stared at us, especially at our hats and boots, as at things of derision—just as, to put it negatively, there were practically no hot rolls and no iced water. Perhaps too, I should add, we didn’t enjoy the works of Mr. Benjamin Haydon, then clustered at the Pantheon in Oxford Street, which in due course became our favourite haunt, so infinitely more, after all, than we had enjoyed those arrayed at the Düsseldorf collection in Broadway; whence the huge canvas of the Martyrdom of John Huss comes back to me in fact as a revelation of representational brightness and charm that pitched once for all in these matters my young sense of what should be.

The American

The American The Wings of the Dove, Volume 1 of 2

The Wings of the Dove, Volume 1 of 2 Frost at Midnight

Frost at Midnight Morning Frost

Morning Frost The Portrait of a Lady — Volume 1

The Portrait of a Lady — Volume 1 Fatal Frost

Fatal Frost The Europeans

The Europeans The New York Stories of Henry James

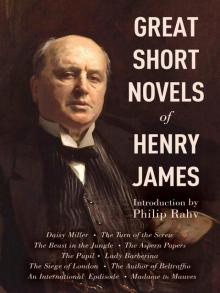

The New York Stories of Henry James Great Short Novels of Henry James

Great Short Novels of Henry James Washington Square

Washington Square The Portrait of a Lady — Volume 2

The Portrait of a Lady — Volume 2 The Ambassadors

The Ambassadors The Wings of the Dove

The Wings of the Dove The Princess Casamassima (Classics)

The Princess Casamassima (Classics) The Coxon Fund

The Coxon Fund First Frost

First Frost Henry James

Henry James The Daily Henry James

The Daily Henry James Travels With Henry James

Travels With Henry James The Reverberator: A Novel

The Reverberator: A Novel What Maisie Knew (Henry James Collection)

What Maisie Knew (Henry James Collection) The Outcry

The Outcry The Marriages

The Marriages The Wings of the Dove, Volume 2

The Wings of the Dove, Volume 2 The Bostonians, Vol. I

The Bostonians, Vol. I The Outcry: -1911

The Outcry: -1911 The Complete Works of Henry James

The Complete Works of Henry James Letters from the Palazzo Barbaro

Letters from the Palazzo Barbaro The Pupil

The Pupil The Bostonians, Vol. II

The Bostonians, Vol. II Pandora

Pandora Glasses

Glasses The Princess Casamassima

The Princess Casamassima What Maisie Knew

What Maisie Knew The Reverberator

The Reverberator The Golden Bowl - Complete

The Golden Bowl - Complete Confidence

Confidence Wings of the Dove (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Wings of the Dove (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) The Spoils of Poynton

The Spoils of Poynton